Health Benefits of Hard Martial Arts in Adults a Systematic Review

1. Introduction

Falls are the second leading cause of death from unintentional injuries worldwide [ane], with the highest prevalence in adults ≥ sixty years of age [1,2]. Falls are related to several factors [two,3], with aging increasing the gamble, which could be related to decreased muscle mass and strength, joint mobility, flexibility, balance, and agility [four], reduced concrete function, and the ability to carry out activities of daily living independently. Information technology has been observed that older adults with markers of frailty (e.g., nether body mass index, cerebral impairment, disability) have upward to 53% greater probability of recurrent falls [5]. On the other hand, balance, defined as a circuitous motor skill derived from the interaction of various sensorimotor processes in guild to control the body in space [6], corresponds to a relevant factor since improvements in static, dynamic, reactive, or multitasking balance can reduce fall take chances in good for you older adults [seven].

The regular exercise of concrete activity (PA) favors the mobility and functional independence of older adults, in addition to improving physical functions (east.g., forcefulness, gait stability, coordination, agility), mental health (eastward.g., cocky-esteem, quality of life) [8], and reduces the risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. It has been reported that PA could also subtract the risk of developing some types of cancer, such equally breast and prostate cancer, and generate healthier aging trajectories associated with metabolic benefits [9]. Systematic reviews accept reported that older adults treated with PA of different types (i.due east., resistance grooming, endurance preparation, multi-component training, balance grooming, exergames) testify improvements in balance ranging from xvi% to 24% [ten] and a lower incidence of falls ranging between 22% and 58% [11,12] compared to control groups without PA.

In addition, the regular practice of PA has achieved greater diffusion in contempo years every bit a strategy for fall prevention and improving or maintaining the general health of older adults living in the customs [13,14] or participating in government programs [15], which contributes to an active and salubrious lifestyle. The strategies to promote active and healthy aging need to be reassessed due to the COVID-19 pandemic to promote the safety practice of PA among older adults, considering, amidst other measures, practicing social distancing [16,17] or training at domicile [xviii]. Such a scenario could provide the opportunity to promote PA that requires a express number of participants in reduced spaces for its practice, such as Olympic combat sports (OCS). In this context, OCS (boxing, fencing, judo, karate, taekwondo, and wrestling) are PA strategies that permit the development of sports practice individually or in pairs in confined spaces through depression-impact dynamic actions with moderate to vigorous intensities using the upper and lower limbs through attack and defense movements, choreographies or specific forms of the disciplines and that can be proficient without contact [19,20]. Likewise, OCS include education about falls and exercises to face them [21] within their basic primary contents and reach an adherence greater than 80% in older adults who practice OCS [19]. To the best of our knowledge, no review has attempted to summarize the currently bachelor literature regarding the potential furnishings of OCS on residual, fall risk, or falls in older adults. Recent systematic reviews accept reported improvements in physical–functional, physiological, and psychoemotional health in older adults who participated in interventions with OCS [19] and a better postural balance in adults who practiced hard martial arts such as taekwondo, judo, karate, soo bahkdo, and ving tsun, compared with groups that participated in dancing, football, running, walking, swimming, and cycling, or did not practice PA [twenty]. Yet, their results are not conclusive due to the diversity of information collection instruments reported by the studies [19] or due to half of the studies analyzed having a cross-sectional pattern [20], amid other factors. In this aspect, a systematic review with a meta-analysis would permit the sample size of unlike studies to be aggregated and can provide not only high-quality testify but also new insights for practitioners that tin can help them make better-informed, show-based decisions regarding the implementation of OCS [22]. Furthermore, a systematic review can help detect gaps and limitations in the scientific literature on OCS, providing valuable data for researchers. Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to assess the bachelor trunk of published peer-reviewed articles related to the furnishings of OCS compared with active/passive controls on residuum, fall hazard, or falls outcomes in older adults.

two. Methods

ii.1. Protocol and Registration

The conduct of this systematic review followed the preferred reporting guidelines for Systematic Review Protocols and meta-analyses PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) [23]. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; code: CRD42021272133).

two.2. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review were original peer-reviewed manufactures without any restriction of linguistic communication or publication appointment, published up to November 2021. Excluded records were conference abstracts, books and volume capacity, editorials, letters to the editor, trial records, reviews, case studies, and essays. In improver, the framework of population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, and study blueprint (PICOs) was followed to incorporate the studies into a systematic review (see Table 1).

2.3. Information and Database Search Process

The search process was performed betwixt Baronial and November 2021, using eight databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, Web of Scientific discipline, Scopus, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO (American Psychological Clan) for social and behavioral Sciences, CINAHL (Cumulative Alphabetize to Nursing and Centrolineal Health Literature) consummate and the collection of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences (EBSCO). The medical subject field headings (MeSH) from the United States of America National Library of Medicine used bias-free language terms related to balance, fall risk, falls, OCS, and older adults. The search string used was the following: ("postural command" OR "postural residuum" OR "balance" OR "postural equilibrium" OR "timed up and go" OR "timed upward-and-go") AND ("fall" OR "falls" OR "faller" OR "roughshod" OR "falling" OR "fall risk" OR "falls risk" OR "chance of falls" OR "fall rates" OR "accidental falls") AND ("boxing" OR "fencing" OR "judo" OR "karate" OR "taekwondo" OR "wrestling" OR "Olympic gainsay sports") AND ("elderly" OR "older adults" OR "older people" OR "older subject" OR "aging" OR "ageing" OR "aged"). The included manufactures and inclusion and exclusion criteria were sent to two contained experts to assist identify additional relevant studies. Nosotros established two criteria that the experts had to meet: (i) to have a Ph.D. in sports sciences; and (ii) to have peer-reviewed publications on aging and/or OCS in impact gene journals co-ordinate to Periodical Citation Reports®. The experts were not provided with our search strategy to avoid skewing their searches. Once all of these steps were completed, on ii November 2021, the databases were searched to retrieve relevant errata or retractions related to the included studies.

2.four. Studies Pick and Information Collection Process

The studies were exported to the EndNote references manager (version X8.ii, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Ii authors (PVB, THV) independently searched, eliminated duplicates, screened titles and abstracts, and analyzed full texts. No discrepancies were found at this stage. The process was repeated for searches within the lists of references and suggestions provided by external experts. Subsequently, potentially eligible studies were reviewed in total text, and reasons for excluding those that did not run across the pick criteria were reported.

two.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of selected studies was assessed with the TESTEX [25], specifically designed for its use in physical exercise-based intervention studies. The TESTEX results were used equally a possible exclusion criterion [25]. It has a fifteen-point scale (v points for study quality and ten points for reporting) [25]. This process was conducted independently by two authors (PVB, THV), and a third author (RRC) acted as a referee in the hundred-to-one cases, which then were validated by some other author (PVB).

2.6. Information Synthesis

The following data from the selected studies were obtained and analyzed: (i) author and publication yr; (two) state of origin; (iii) study design; (4) initial health of the sample; (v) number of participants in the intervention and command groups; (six) mean age of the sample; (7) activities developed in the OCS groups and control groups; (8) training volume (total duration, weekly frequency and time per session); (ix) training intensity; (10) data collection instruments of residuum; (xi) data collection instruments of fall hazard or falls; and (xii) the main outcomes of the studies.

2.7. Summary Measures for Meta-Assay

Meta-analyses were included in the report protocol, with full details bachelor at PROSPERO, registry lawmaking CRD42021272133. All the same, the low number of includable studies reporting data for the same event or similar testing procedures precluded a robust meta-analysis.

two.8. Certainty of Evidence

The studies were assessed for the certainty of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) scale [26] and were classified as having a high, moderate, low, or very low certainty of bear witness. All analyses started with a grade of high certainty due to including studies with experimental pattern (randomized controlled trial and non-randomized controlled trial) and were downgraded if there were concerns over the risk of bias, consistency, precision, directness of the outcomes, or risk of publication bias [26]. Due to the pocket-sized number of studies, the run a risk of publication bias was not assessed [27]. Two authors (PVB, THV) independently assessed the studies, and whatsoever discrepancies were resolved through consensus with a third writer (RRC).

3. Results

iii.1. Report Selection

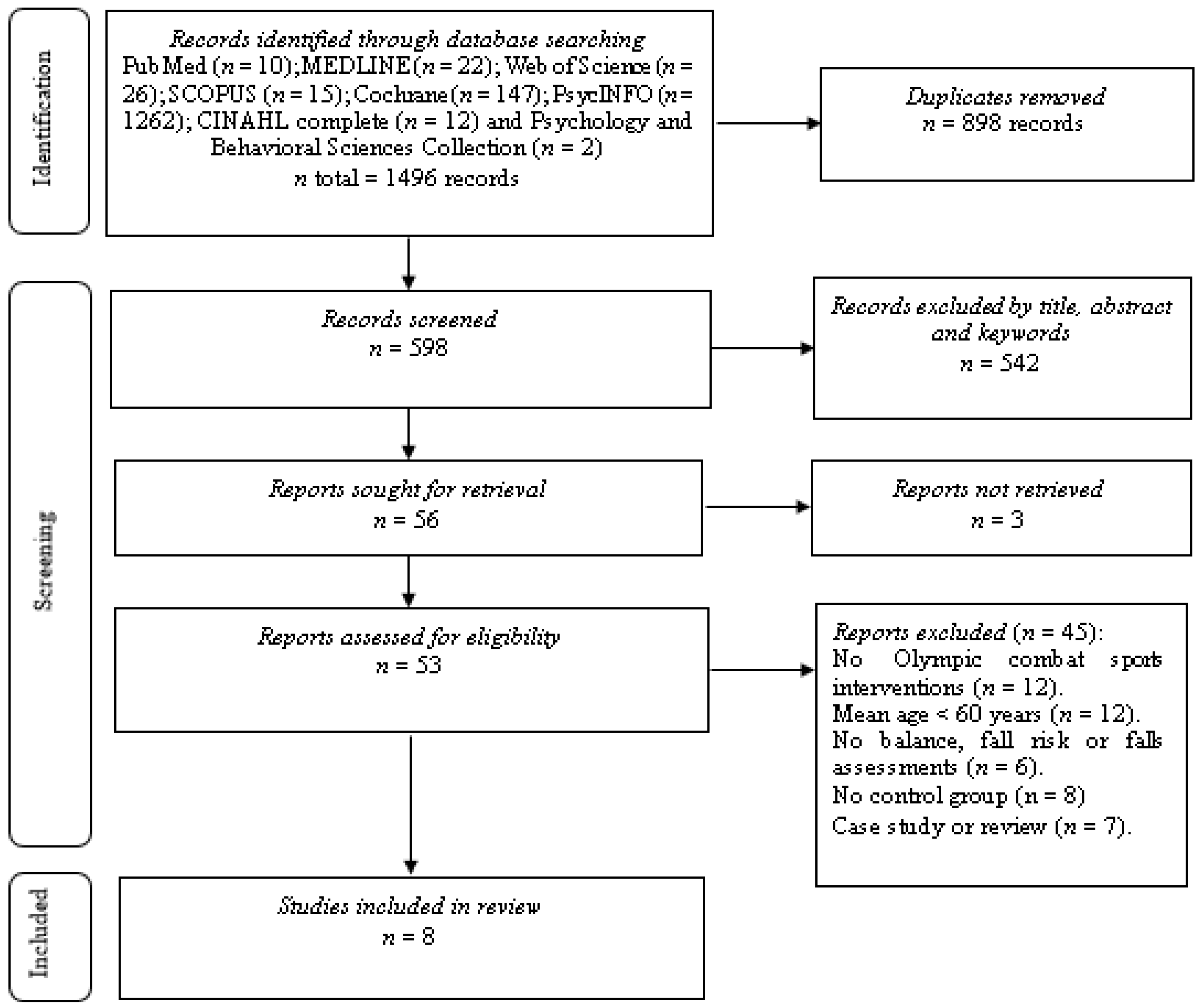

Figure 1 details the search process for the studies. A full of 1496 records were institute in the study identification stage. Subsequently, duplicates were eliminated, and the studies were filtered past selecting the championship, abstruse, and keywords, resulting in 598 references. A total of 56 studies were included the next phase of the analysis, 3 of which were excluded as the texts were inaccessible (authors of inaccessible studies were contacted requesting a copy of their manuscript, estimating 30 days equally a maximum response time). 50-three studies were analyzed via the full text, 12 of which were excluded due to not existence OCS interventions, 12 due to the mean historic period of the sample being lower than 60 years, six for not having assessments of residual, fall risk, or falls, 8 for not having a command grouping, and seven for being case studies or reviews. Later on this process, the full number of studies that met all selection criteria was eight [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

3.2. Methodological Quality

The 8 selected studies were analyzed using the TESTEX scale (Table 2). All of the studies accomplished a score equal to or greater than lx% of the scale, specifically: nine/15 [29,33], 10/15 [28,35], eleven/15 [30], 12/xv [31,34], and 13/15 [32], indicating a moderate to high methodological quality, then no studies were excluded from the systematic review.

3.3. Risk of Bias inside Studies

The certainty of evidence was assessed with the GRADE scale. The risk of bias was considered with some concerns in four studies [xxx,32,34,35] and high take chances in iv studies [28,29,31,33]. Five studies presented some concerns for the randomization process [28,thirty,32,34,35] and three with high risks of bias not randomizing the groups [29,31,33]. Three studies were assessed with some concerns for missing outcomes due to non reporting the post-assessment for some outcomes [29,31,33], and v studies were rated every bit having a low run a risk of bias [28,30,32,34,35]. All studies were assessed with some concerns for selecting the reported result as there was no pre-registered protocol and a low risk of bias for deviations from intended intervention-effects of assignment to intervention and measurement of the outcome (Table 3).

3.iv. Studies Characteristics

Table 4 summarizes the variables analyzed in each of the selected studies. Of these, 3 were developed in Republic of korea [28,30,35], two in the United States of America [32,33], one in Spain [29], one in Italy [31], and one in Germany [34]. Regarding the design of the studies, five were randomized controlled trials [28,thirty,32,34,35], and iii were non-randomized controlled trials [29,31,33].

3.5. Sample Characteristics

One study had 24 participants [28], six had 30 to 40 [29,xxx,31,32,33,35], and one had 90 participants [34], totaling a sample of 322 older adults (64% female) with a mean age of 71.one years. Regarding the initial wellness of the participants, seven studies report that the older adults included were people with no apparent health problems [28,29,30,31,33,34,35], which complements the groups of Campos-Mesa et al. [29], indicating that their participants are also pre-frail older adults. Merely one report involved older adults with Parkinson's affliction [32]. Three studies indicated that their participants had no prior experience in OCS when initiating the interventions [30,31,33], and five studies did non report on their participants' prior experience in OCS [28,29,32,34,35]. V studies reported on the history or autumn hazard in older adults, and two of these indicated that xc% of the participants had suffered a fall in the past vi months [33] or at some point before their fall inclusion in the study [29]. Ane report reported that the maximum number of falls in its participants was three last twelvemonth [34]. Two studies indicated that their participants had a low fall risk according to the Berg Balance Scale (BBS) with mean scores of 49 [32] and 55 points [31]. Three studies did non report their participants' history or fall take chances [28,30,35].

3.6. Interventions Conducted and Dosing

Six studies had two groups of analysis [28,29,30,31,32,33]: an experimental grouping that participated in the intervention with OCS and a control group that maintained the usual activities of daily living [28,xxx,31,33] or participated in physical fitness programs which were focused on exercises and activities to develop endurance, muscle forcefulness, cardiorespiratory fitness, flexibility, agility, and remainder [29,32]. Two studies included iii groups [34,35], one OCS grouping, one command group that maintained the usual activities of daily living, and a third group that, in the instance of Witte et al. [34], participated in physical fettle (focused on activities to develop endurance, muscle strength, cardiorespiratory fettle, flexibility, agility, and residual) and in the case of Youm et al. [35], in walking practise.

Apropos the activities adult in the OCS interventions, four studies used taekwondo [28,30,33,35], including technical foundations such as basic postures (short stride, long stride, and rider position), displacements (forward, backward, and side shifts), punches, blocks (low, medium, and high), and kicks (forepart, roundhouse, and descending), performed individually and in pairs, in addition to modality-specific choreographies or forms (Poomsae) [28,30,33,35]. 2 studies applied judo training [29,31], including calorie-free routines and dynamic movements of the whole torso, imitating judo techniques, followed by judo-specific passive and active continuing and ground techniques, performed individually and in pairs, to finish with choreography or specific forms of judo [29,31]. I study used boxing as an intervention modality [32], reporting specific cardiorespiratory fitness activities distributed as a grooming excursion, without detailing the exercises, merely following recommendations from previous studies [36] and noting that the participants used gloves and punching bags without making contact with other people while boxing [32]. Meanwhile, Witte et al. [34] used karate as an intervention modality through various postures (forwards, backward, and straddle legs), displacements with arm techniques during continuing (fist blows, blocks, and finger accident), and kicking. In addition, the participants learned uncomplicated attack and defense exercises with their partners and a uncomplicated choreography or kata [34]. In our systematic review, no studies that used fencing or wrestling as an intervention modality for older adults were found.

Regarding the people who led the sessions with OCS, four studies reported that instructors or experienced professionals in the described modalities conducted them [29,xxx,31,32], while four studies did not state who was in accuse of leading the sessions with OCS [28,33,34,35].

Regarding the elapsing of the interventions with OCS, ane lasted for six weeks [29], 6 lasted between 11 and xvi weeks [28,30,31,32,33,35], and one lasted for 20 weeks [34]. Regarding the preparation frequency, seven studies reported a weekly distribution of two and three sessions [28,29,31,32,33,34,35], and one had five weekly sessions [xxx]. The duration of the sessions was 60 min [28,29,thirty,31,33,34,35], while ane study reported a 90 min grooming session [32]. Iii studies reported grooming intensity, 2 through the percent of maximum heart rate (%HRmax), specifically between xl and lx%HRmax [35] and between 50 and 80%HRmax [xxx], while Ciaccioni et al. [31], reported it equally moderate to vigorous.

3.vii. Data Collection Instruments of Balance

Four studies used the Timed Up-and-Become (TUG) examination [28,xxx,32,33]. Furthermore, Combs et al. [32] used the Activities-specific Residue Confidence scale and Dual-task Timed Up-and-Go test, while Cromwell et al. [33] included the Gait Stability Ratio, which is where the length of time a participant stands on i leg is recorded with a stopwatch, alongside the Multidirectional Reach Examination. For their part, Witte et al. [34] only considered the Motor Residuum Test, and Youm et al. [35] measured variables of the heart of force per unit area with a force platform by requesting the participants to go along their eyes open.

3.eight. Information Collection Instruments of Fall Take a chance or Falls

Two studies used the Falls Efficacy Scale-International [29,31], which was complemented by Campos-Mesa et al. [29] with the World Health System (WHO) Questionnaire for the study of falls in the older adults. In addition, two studies used the BBS [31,32], while Cromwell et al. [33] used a dichotomous question about fear of falling.

3.9. Balance

Although the low number of includable studies reporting data for the same upshot precluded a robust meta-assay, 6 studies reported balance every bit the master outcome, and four studies provided TUG data (i.e., fourth dimension), involving four OCS and four command groups that were compared (pooled n = 132). The results showed similar changes in TUG subsequently OCS compared to passive and active controls (ES = −0.27, small; 95% CI = -0.61 to 0.06; p = 0.112; Itwo = 0.0%; Egger's test, p = 0.281). On the other hand, when analyzing the individual results for TUG, two studies reported a significant subtract (p < 0.05) in the execution time in favor of the participants who intervened with OCS compared to control groups [28,33], and ii studies showed no divergence between the groups with OCS compared to command groups that maintained the usual activities of daily living [30] and participated in physical fitness [32].

In the instance of Combs et al. [32], a significant increase (p = 0.015) in the total score of the Activities-specific Rest Confidence scale was reported in favor of the group with physical fitness compared to the group with OCS, just with no differences reported in Dual-task Timed Upwards-and-Go test in older adults with Parkinson'southward disease. For their part, Cromwell et al. [33] reported a significant increment (p < 0.05) in the Multidirectional Accomplish Test and a significant subtract (p < 0.05) in the Gait Stability Ratio in favor of the group with OCS compared to the control (passive) grouping, without reporting differences in the time of standings on one leg. In the case of Witte et al. [34], in that location were no differences in the dynamic and static balance between the group with OCS vs. control group (passive), only in that location was a pregnant pre- and mail service-intervention improvement of the dynamic balance in the group with OCS (p = 0.015) and in the passive group (p = 0.018). The study by Youm et al. [35] reported a significant comeback in balance in the groups with OCS and walking exercise compared to the command grouping (passive) (p < 0.05), reflected by the decrease in variables such as the root mean foursquare, speed, and area of the center of pressure both in the mediolateral and anteroposterior directions. In summary, of the six studies analyzed, two reported favorable residue changes for the groups with OCS vs. passive groups [28,33].

iii.10. Fall Risk or Falls

Four studies reported a fall gamble or falls equally the main outcome. Although two studies used the BBS to assess older adults [31,32], just 1 reported post-intervention results. No differences were found betwixt the group with OCS vs. the group with physical fitness for the BBS, but there were significant improvements (p = 0.005) pre- and post-intervention independently in both groups of older adults with Parkinson'south disease [32]. Two studies were evaluated with the Falls Efficacy Scale-International; on the one hand, Campos-Mesa et al. [29] reported a significant subtract (p = 0.002) in fear of falling in favor of the grouping intervened with OCS compared to the grouping with physical fitness, while Ciaccioni et al. [31], did not attain pregnant changes in the Falls Efficacy Scale-International. Finally, 2 assessments were not used to measure post-intervention, specifically, the WHO Questionnaire [29] and the dichotomous question on fear of falling [33]. In summary, no differences were plant between the groups that intervened with OCS vs. the control groups of the four studies that reported fall risk or falls.

iii.xi. Certainty of Evidence

The limitations related to the certainty of evidence prevent a recommendation for or against the employ of OCS equally interventions that favor remainder, reduce autumn risk, or reduce falls in older adults (Tabular array 5).

3.12. Agin Events and Adherence

The analyzed studies did not written report adverse events (injuries) in older adults who participated in the OCS interventions. Three studies did not report attrition in judo [29] and taekwondo [33,35] interventions regarding adherence. Four studies achieved adherence equal to or greater than 84% in interventions with taekwondo [28,30], judo [31], and karate [34]. Only one study reported a 64% adherence to boxing [32]. The chief reasons for attrition were personal issues, not complying with the minimum omnipresence at training sessions, or an unsupported schedule [28,29,31,32,33,35]. One study added the loss of involvement of older adults with Parkinson's illness to these reasons [32], while two studies did not report the reasons for attritions [xxx,34].

4. Word

The nowadays systematic review aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of OCS on balance, autumn hazard, or falls in older adults. The systematic review identified eight studies with a methodological quality ≥ 60% of the established score. However, the certainty of testify was rated very low. Therefore, information technology is impossible to institute a definitive recommendation for or against OCS interventions as an effective strategy to improve balance, reduce autumn risk, or falls in older adults.

Regarding balance, it was only possible to perform a meta-analysis of the TUG data [28,30,32,33] without finding changes in favor for or confronting the groups with OCS vs. active or passive command groups (ES = −0.27). Private studies reported significant improvements (p < 0.05) in the groups that intervened with OCS at the fourth dimension of the TUG test [28,32,33], Gait Stability Ratio [33], variables of the eye of pressure [35], Activities-specific Balance Confidence scale [32], and dynamic balance [34]. It has been suggested that i of the factors that would cause a deterioration in balance in older adults would exist lower functionality of the lower limbs due to a loss of muscle mass and forcefulness, the aging of biomechanical elements of the musculoskeletal system, a decreased range of motion of the ankle, and less elasticity of the foot tissues, which would limit sensory feedback [thirteen]. Furthermore, poor residuum in older adults has been associated with a delay in muscular responses triggered by proprioceptive deficits that are role of the aging procedure [37]. Therefore, practicing PA that involves sensorimotor stimuli could favor rest [x,20] through dissimilar preparation methods, such as soft [38] and hard [20] martial arts.

Iv of the analyzed studies evaluated the fall risk, or falls, using the BBS [31,32], Falls Efficacy Calibration-International [29,31], WHO Questionnaire [29] or a dichotomous question well-nigh fear of falling [33]; in some cases, it was assessed post-intervention [29,33]. However, two studies reported a significant reduction (p < 0.01) in the fall risk [32] and a fright of falling [29]. The cause for falls are multifactorial [2,3], requiring a multidimensional intervention for autumn prevention [2]. In addition, it has been indicated that balance, mobility, medication, and psychological, sensory, and neuromuscular aspects are predictive factors of recurrent falls in older adults [5]. In this sense, reducing the fall risk and fear of falling through OCS is auspicious since it has been proposed as a simple and inexpensive solution to teach people about falling safely as early on equally possible in their lives [21] and in an elementary content in almost OCS.

On the other hand, the results of our systematic review are aligned with previous systematic reviews that have reported some improvements and the maintenance of balance in adults who practice hard martial arts [20] and meaning improvements (p = 0.017) in lower limb force measured through the chair stand exam in older adults in the intervention with OCS grouping compared to command groups without PA [19]. Muscle strength is a physical quality that has been linked to a more outstanding balance and lower fall hazard in aging [4,11], which is considered a basic element in programs focused on fall prevention in older adults [10,xiv]. Therefore, information technology is essential to promote PA amongst older adults, which focuses on the strengthening of the large muscle groups, cardiorespiratory fitness, and rest [fifteen], since an adverse event has been seen in residue that ranges from 14.9% to 21.9% in groups without PA [10] and a decrease in falls (31–35%) in older adults participating in community PA programs compared to passive control groups [14]. In this sense, OCS may meliorate older adults' well-being and general health status [xix], musculus strength, cardiorespiratory fitness, and balance. In add-on, OCS interventions involve teaching about falls, including exercises to forestall and avoid adverse effects during falls (i.due east., fall-technique drills) [21]. For these reasons, the OCS would positively impact older adults' functional independence and quality of life [nineteen,39].

Regarding the certainty of evidence, our systematic review reported it as very low, without allowing u.s.a. to establish definitive recommendations, a situation that coincides with a meta-analysis focused on resistance training as a method for fall prevention in older adults [12]. Similarly, systematic reviews with soft martial arts such equally tai chi in older adults [38] and with hard martial arts in adults [20] have reported that the methodological quality of the studies selected is moderate to low. Therefore, they recommend because their results with caution. In contrast, bibliometric reviews with OCS have reported a significant number of studies published in the Web of Science; for example, judo was reported in 383 indexed articles between 1956 and 2011 [40], and taekwondo in 340 articles between 1988 and 2016 [41]; despite the increasing productivity on OCS, the certainty of evidence of the studies establish in our systematic review is depression. Future studies with OCS should use double-blind randomization and supervised control groups among other methodological strategies, equally well as reporting all post-intervention results, and previously register their research protocols [26], which would help to improve the quality of their research designs and, consequently, the certainty of evidence.

Regarding the dosage used for the OCS interventions, average values of 12 weeks were presented, with two to iii weekly sessions of 60 min, while iii studies reported the intensity as using xl–eighty%HRmax [xxx,35] or moderate to vigorous activity [31]. The frequency and intensity reported by the studies with OCS align with the international PA recommendations for older adults [4,42]. The activities selected in the OCS interventions were based on basic technical foundations of the disciplines (boxing, judo, karate, and taekwondo); no agin effects were reported, and they achieved a hateful adherence >80%. With the advisable dosage and selection of activities, OCS can run into the PA level that older adults need each day [19]. Otherwise, iv of the selected studies reported that the sessions with OCS were led by instructors or experienced professionals in the described modalities [29,thirty,31,32]. Having instructors or experienced professionals in OCS can guarantee safety exercise due to the high incidence of injuries that their sports do (elite competition) generates, existence the well-nigh recurrent in the head (45.viii%) for battle, in the knees (24.eight%) for wrestling, in the fingers (22.8%) for taekwondo and in the lower back (10.nine%) for judo [43]. Also, due to the variety of technical foundations (e.1000., postures, displacements, blows, projections, kicks) that make up the contents of the OCS, this negates the higher risk of injury due to poor execution and requires adaptations to be fabricated to the activities and then that older adults tin can perform them; therefore, permanent preparation of instructors or professionals in accuse of directing grooming with combat sports has been suggested to accomplish the greatest benefits [44]. In this sense, previous systematic reviews have suggested selecting combat sports according to people's interests and initial health statuses [xix,xx], every bit well every bit not-contact activities, practiced individually or in pairs through choreographies or forms according to the level of experience in OCS and the age range of older adults [19], respecting the bones training principles such as progressive overload with a moderate to vigorous intensity and a frequency of 2 to three weekly sessions of 60 min [19], for safe exercise. The background is aligned with what was reported in the studies analyzed in our systematic review. The main limitation of our systematic review is the low certainty of evidence found, like to previous systematic reviews in the field of martial arts and combat sports [20,38]. In addition, the low number of includable studies reporting information for the same outcome or with similar testing procedures precluded a robust meta-analysis for the furnishings of OCS on rest, fall risk, or falls. The facts prove that OCS practice in older adults is an emerging field that needs more support and enquiry [xix]. Considering the responses obtained in the present systematic review, OCS practise in older adults could be condom and relevant to improving health, given the studies discussed. In addition, OCS are low-cost and affordable PA strategies, requiring reduced space, little implementation, and motivating older adults due to the diversity of technical foundations and activities carried out [nineteen,twenty,21]. However, due to the heterogeneity of the studies included in this systematic review, it is incommunicable to establish a definitive recommendation for OCS interventions to improve residue and reduce the fall risk or number of falls in older adults. As best-selling by the authors, no studies compared individuals who started OCS later on 60 years of age with individuals who skilful OCS during several stages of life. The responses of these studies may exist different amidst participants who started OCS in the aging phase compared to the older adults who had practiced OCS since adolescence and young adulthood. Such responses may exist different due to the stimulus performed, i.e., frequency, book, intensity, density, and other physical exercises conducted in parallel (e.g., weightlifting, endurance training, high-intensity interval training), which would probably help develop concrete fettle. The sample size of the studies with OCS oftentimes uses competitive athletes or physically active people seeking wellness and quality of life or recreation. Due to this, the comparison and management of our systematic review findings remain limited with which to provide an accurate diagnosis, promoting simply speculations.

five. Conclusions

The available evidence does not allow a definitive recommendation for or against OCS interventions every bit an effective strategy to better residuum and reduce the fall risk or falls in older adults. Therefore, more than high-quality studies are required to describe definitive conclusions.

Author Contributions

P.5.-B., R.R.-C. and T.H.-Five. wrote the kickoff draft of the manuscript; P.V.-B., R.R.-C. and T.H.-V. collected information; P.V.-B., R.R.-C., T.H.-V. and B.H.M.B. analysed and interpreted the data; Due east.G.-1000., Thousand.M.-R., Y.C.-C. and J.H.-M. revised the original manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Argument

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Information Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current review are available from the Respective writer upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Falls. 2021: Geneva, Swiss. Available online: https://world wide web.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/falls (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Park, S.-H. Tools for assessing fall gamble in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crumbling Clin. Exp. Res. 2018, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfortmueller, C.; Lindner, G.; Exadaktylos, A. Reducing fall hazard in the elderly: Risk factors and autumn prevention, a systematic review. Minerva Med. 2014, 105, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fragala, M.Due south.; Cadore, Due east.L.; Dorgo, S.; Izquierdo, M.; Kraemer, Due west.J.; Peterson, M.D.; Ryan, E.D. Resistance training for older adults: Position argument from the national strength and workout association. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2019–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehu, D.; Davis, J.; Falck, R.; Bennett, K.; Tai, D.; Souza, M.; Cavalcante, B.; Zhao, M.; Liu-Ambrose, T. Risk factors for recurrent falls in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Maturitas 2020, 144, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horak, F.B. Postural orientation and equilibrium: What do we need to know about neural control of residuum to forestall falls? Historic period Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. 2), ii7–ii11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lesinski, M.; Hortobágyi, T.; Muehlbauer, T.; Gollhofer, A.; Granacher, U. Effects of residual training on balance performance in salubrious older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1721–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, C.; O'Sullivan, R.; Caserotti, P.; Tully, M.A. Consequences of concrete inactivity in older adults: A systematic review of reviews and meta-analyses. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Battaglia, K.; Patti, A.; Brusa, J.; Leonardi, Five.; Palma, A.; Bellafiore, 1000. Physical activity programs for rest and fall prevention in elderly: A systematic review. Medicine 2019, 98, e16218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadore, E.L.; Rodríguez-Mañas, Fifty.; Sinclair, A.; Izquierdo, M. Furnishings of different exercise interventions on risk of falls, gait ability, and balance in physically fragile older adults: A systematic review. Rejuvenation Res. 2013, 16, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claudino, J.; Afonso, J.; Sarvestan, J.; Lanza, Yard.; Pennone, J.; Filho, C.; Serrão, J.; Espregueira-Mendes, J.; Vasconcelos, A.; de Andrade, M.; et al. Force training to foreclose falls in older adults: A systematic review with meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Med. 2021, ten, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neville, C.; Nguyen, H.; Ross, K.; Wingood, M.; Peterson, Due east.Due west.; DeWitt, J.E.; Moore, J.; Male monarch, K.J.; Atanelov, L.; White, J.; et al. Lower-limb factors associated with balance and falls in older adults: A systematic review and clinical synthesis. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2020, 110, Article_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klima, D.Westward.; Rabel, M.; Mandelblatt, A.; Miklosovich, M.; Putman, T.; Smith, A. Community-based fall prevention and exercise programs for older adults. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2021, ten, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Badilla, P.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, M.; Vargas-Vitoria, R.; López-Fuenzalida, A. Effects of physical activity governmental programs on health status in contained older adults: A systematic review. J. Aging Phys. Human action. 2019, 27, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Câmara, G.; Arriaga, M.; Nogueira, P.; Miguel, J.P. Active and salubrious aging afterwards COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal and other European countries: Time to rethink strategies and foster action. Front. Public Wellness 2021, 9, 700279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaabene, H.; Prieske, O.; Herz, Chiliad.; Moran, J.; Höhne, J.; Kliegl, R.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Behm, D.; Hortobágyi, T.; Granacher, U. Habitation-based exercise programs improve concrete fettle of good for you older adults: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis with relevance for COVID-19. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 67, 101265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakicevic, N.; Moro, T.; Paoli, A.; Roklicer, R.; Trivic, T.; Cassar, Southward.; Drid, P. Stay fit, don't quit: Geriatric Exercise Prescription in COVID-19 Pandemic. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Badilla, P.; Herrera-Valenzuela, T.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Aedo-Muñoz, E.; Martín, E.B.-Due south.; Ojeda-Aravena, A.; Branco, B. Effects of Olympic gainsay sports on older adults' health status: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Origua Rios, S.; Marks, J.; Estevan, I.; Barnett, Fifty.M. Health benefits of hard martial arts in adults: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobosz, D.; Barczyński, B.J.; Kalina, A.; Kalina, R.M. The almost effective and economic method of reducing death and disability associated with falls. Curvation. Budo 2018, fourteen, 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, M.H.; Asi, Due north.; Alsawas, M.; Alahdab, F. New evidence pyramid. Evid. Based Med. 2016, 21, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, Chiliad.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.Eastward.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 argument: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health. 2015: Geneva, Swiss. Bachelor online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186463 (accessed on 27 December 2021).

- Smart, Northward.; Waldron, M.; Ismail, H.; Giallauria, F.; Vigorito, C.; Cornelissen, 5.; Dieberg, Thousand. Validation of a new tool for the assessment of written report quality and reporting in practise training studies: TESTEX. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, ix–xviii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; et al. Form guidelines: 1. Introduction—Grade bear witness profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Sutton, A.J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Terrin, Due north.; Jones, D.R.; Lau, J.; Carpenter, J.; Rucker, Thousand.; Harbord, R.M.; Schmid, C.H.; et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, S.H.; Hong, G.R.; Min, D.G.; Kim, E.H.; Park, S.K. Effects of functional fitness enhancement through taekwondo grooming on physical characteristics and risk factors of dementia in elderly women with low. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Mesa, M.C.; DelCastillo-Andrés, O.; Toronjo-Hornillo, L.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C. The effect of adapted utilitarian Judo, as an educational innovation, on fear-of-falling syndrome. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Southward.-Y.; Roh, H.-T. Taekwondo enhances cognitive part equally a upshot of increased neurotrophic growth factors in elderly women. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, xvi, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaccioni, South.; Capranica, L.; Forte, R.; Chaabene, H.; Pesce, C.; Condello, Yard. Effects of judo training on functional fitness, anthropometric, and psychological variables in old novice practitioners. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, S.A.; Diehl, M.D.; Chrzastowski, C.; Didrick, N.; McCoin, B.; Mox, N.; Staples, W.H.; Wayman, J. Customs-based group exercise for persons with Parkinson disease: A randomized controlled trial. NeuroRehabilitation 2013, 32, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cromwell, R.L.; Meyers, P.M.; Meyers, P.E.; Newton, R.A. Tae Kwon Do: An constructive exercise for improving balance and walking ability in older adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Eddy. Sci. Med Sci. 2007, 62, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, 1000.; Emmermacher, P.; Pliske, G. Comeback of residual and full general physical fettle in older adults by Karate: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Med. Res. 2017, 24, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youm, C.; Lee, J.-S.; Seo, Grand.E. Effects of Taekwondo and walking exercises on the double-leg residue control of elderly females. Korean J. Sport Biomech. 2011, 21, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, S.A.; Diehl, Thousand.D.; Staples, W.H.; Conn, L.; Davis, K.; Lewis, N.; Schaneman, G. Boxing preparation for patients with Parkinson disease: A case series. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, R.A.; Contreras-Vidal, J.Fifty.; Paloski, Due west.H. Cortical control of upright stance in elderly. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2018, 169, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, Ten.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Xia, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Jin, R. Tai Chi for improving residue and reducing falls: An overview of 14 systematic reviews. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 63, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Dudley, D.; Woodcock, S. The effect of martial arts grooming on mental health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2020, 24, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peset Mancebo, Thou.F.; Ferrer Sapena, A.; Villamón Herrera, G.; González Moreno, Fifty.M.; Toca Herrera, J.-Fifty.; Aleixandre Benavent, R. Scientific literature analysis of Judo in Web of Science. Arch. Budo 2013, 9, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gutiérrez, M.; Valdés-Badilla, P.; Gutiérrez-García, C.; Herrera-Valenzuela, T. Taekwondo scientific product published on the web of scientific discipline (1988-2016): Collaboration and topics. Movimento 2017, 23, 1325–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Willumsen, J.F. World Health Arrangement 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, S.J.; Drew, M.K.; Talpey, S.; McIntosh, A.S.; Finch, C.F. A systematic review of prospective epidemiological research into injury and illness in Olympic combat sport. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 52, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujak, Z.; Gierczuk, D.; Litwiniuk, Southward. Professional activities of a coach of martial arts and combat sports. J. Combat. Sports Martial Arts 2013, four, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. Flowchart of the review process. Legends: Based on PRISMA guidelines [23].

Figure i. Flowchart of the review process. Legends: Based on PRISMA guidelines [23].

Table 1. Selection criteria used in the systematic review.

Table 1. Selection criteria used in the systematic review.

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Older adults, considered as older adult participants with an average age of threescore years or more according to the Earth Health Organisation [24], and without distinction of sex. | People under sixty years of age. |

| Intervention | Interventions with Olympic combat sports (boxing, fencing, judo, karate, taekwondo, wrestling) lasting four weeks or more. | Exercise interventions not involving Olympic combat sports. |

| Comparator | Interventions that had a control group with or without supervised physical activity. | Absence of control grouping. |

| Consequence | At least one balance assessment (e.g., forcefulness platform, timed up-and-get test), autumn risk, or falls assessment (e.g., Falls Efficacy Scale-International, Berg Balance Scale) before and after the intervention. | Lack of baseline and/or follow-upwardly data. |

| Study design | Studies with experimental blueprint (randomized controlled trial and not-randomized controlled trial) with pre- and mail service-assessment. | Cantankerous-sectional, retrospective, and prospective studies. |

Tabular array 2. Written report quality assessment according to TESTEX scale.

Table 2. Study quality assessment co-ordinate to TESTEX calibration.

| Report | Eligibility Criteria Specified | Randomly Allocated Participants | Allocation Concealed | Groups Like at Baseline | Assessors Blinded | Outcome Measures Assessed >85% of Participants * | Intention to Treat Analysis | Reporting of between Group Statistical Comparisons | Point Measures and Measures of Variability Reported ** | Activity Monitoring in the Control Grouping | Relative Exercise Intensity Reviewed | Exercise Book and Free energy Expended | Overall TESTEX # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek et al. [28] | Yes | Aye | Unclear | Yeah | Unclear | Aye (2) | Yes | Yes | Yes (2) | No | No | Yes | 10/15 |

| Campos-Mesa et al. [29] | Yes | No | Unclear | Yeah | Unclear | Yep (1) | Yep | Yes | Yes (two) | Yes | No | Yes | 9/15 |

| Cho & Roh [30] | Yes | Yeah | Yep | Yep | Unclear | Yeah (2) | Yep | Yep | Yeah (1) | No | Yes | Yeah | 11/15 |

| Ciaccioni et al. [31] | Aye | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Aye (3) | Yeah | Yes | Yes (ii) | No | Yes | Yes | 12/fifteen |

| Combs et al. [32] | Yes | Yep | Yes | Aye | No | Yes (3) | Yes | Yeah | Aye (2) | Yes | No | Yes | xiii/fifteen |

| Cromwell et al. [33] | Yes | No | Unclear | Yes | Yep | Yep (2) | Yes | Yes | Aye (one) | No | No | Yes | 9/xv |

| Witte et al. [34] | Yes | Yes | Aye | Yes | No | Yes (3) | Yeah | Yep | Yep (2) | No | No | Yes | 12/15 |

| Youm et al. [35] | Yes | Yeah | Unclear | Yep | Unclear | Yes (ane) | Yes | Yes | Yes (2) | No | Yes | Yes | 10/fifteen |

Table three. Risk of bias within studies.

Table 3. Take chances of bias inside studies.

| Study | ane | 2 | 3 | 4 | five | Overall GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baek et al. [28] | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Some concerns | High risk |

| Campos-Mesa et al. [29] | High risk | Low take a chance | Some concerns | Low take chances | Some concerns | High adventure |

| Cho & Roh [xxx] | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low chance | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Ciaccioni et al. [31] | Loftier take a chance | Low gamble | Some concerns | Depression adventure | Some concerns | Loftier risk |

| Combs et al. [32] | Some concerns | Low gamble | Low risk | Depression risk | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Cromwell et al. [33] | High risk | Low risk | Some concerns | Low risk | Some concerns | Loftier hazard |

| Witte et al. [34] | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Depression gamble | Some concerns | Some concerns |

| Youm et al. [35] | Some concerns | Low risk | Low risk | Low take a chance | Some concerns | Some concerns |

Table 4. Studies reporting on the effectiveness of Olympic gainsay sports on balance, fall risk, or falls in older adults.

Table 4. Studies reporting on the effectiveness of Olympic combat sports on balance, fall risk, or falls in older adults.

| Report | Country | Study Pattern | Sample's Initial Health | Groups | Mean Historic period (Year) | Activities in the Intervention and Control Groups | Preparation Volume | Training Intensity | DCI of Balance | DCI of Fall Chance or Falls | Primary Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | TD (Weeks) | Fr | TPS (min) | ||||||||||

| (Weekly) | |||||||||||||

| Baek et al. [28] | South Korea | RCT | Apparently healthy | TUG | None | EG vs. CG: ↓ TUG (in favour EG). | |||||||

| EG: 12 | 72.vi | EG: taekwondo | 12 | 3 | 60 | NA | |||||||

| CG: 12 | 72.iv | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | NA | ||||||||

| Campos-Mesa et al. [29] | Spain | NRCT | Apparently salubrious | None | FES-I | EG vs. CG: ↓ FES-I π (in favour EG). | |||||||

| EG: nineteen | 74.3 | EG: judo | 6 | 2 | sixty | NA | WHO Questionnaire | WHO Questionnaire was not reported post-intervention. | |||||

| CG: 11 | 77.8 | CG: concrete fitness | 2 | threescore | NA | ||||||||

| Cho & Roh [30] | Republic of korea | RCT | Apparently healthy | 50–fourscore%HRmax | TUG | None | |||||||

| EG: 19 | 68.9 | EG: taekwondo | 16 | 5 | 60 | ||||||||

| EG vs. CG: ↔ TUG. | |||||||||||||

| CG: 18 | 69 | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | |||||||||

| Ciaccioni et al. [31] | Italian republic | NRCT | Patently salubrious | Moderate to vigorous | None | FES-I | EG vs. CG: ↔ FES-I π. | ||||||

| EG: 19 | 69.3 | EG: judo | 16 | 2 | threescore | ||||||||

| BBS | BBS was non reported mail service-intervention. | ||||||||||||

| CG: 21 | seventy.ii | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | |||||||||

| Combs et al. [32] | U.s. of America | RCT | Parkinson' 's disease | BBS | |||||||||

| EG: 17 | 66.5 | EG: boxing | 12 | 2–3 | 90 | NA | ABC TUG | EG vs. CG: ↑ ABC (in favour CG), ↔ Bulletin board system, ↔ TUG, ↔ DTUG. | |||||

| DTUG | |||||||||||||

| CG: xiv | 68 | CG: physical fettle | 2–3 | xc | NA | ||||||||

| Cromwell et al. [33] | U.s.a. of America | NRCT | Obviously healthy | I question | |||||||||

| EG: 20 | 72.7 | EG: taekwondo | 11 | ii | 60 | NA | TUG | EG vs. CG: ↓ TUG, ↑ MDRT, ↓ GSR, ↔ SLS (in favour EG). | |||||

| MDRT | |||||||||||||

| CG: 20 | 73.8 | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | NA | GSR | One question was not reported mail-intervention. | ||||||

| SLS | |||||||||||||

| Witte et al. [34] | Deutschland | RCT | Apparently healthy | MBT (static and dynamic residue) | None | EG vs. FG vs. CG: ↔ Static residual, ↔ Dynamic balance. | |||||||

| EG: 30 | EG: karate | two | threescore | NA | |||||||||

| FG: thirty | 69.3 | FG: physical fitness | 20 | 2 | 60 | NA | |||||||

| CG: thirty | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | NA | |||||||||

| Youm et al. [35] | South Korea | RCT | Apparently healthy | 12 | None | EG vs. WG vs. CG: ↔ AP RMS altitude, ↔ AP velocity, ↔ AP total power frequency, ↓ ML RMS distance, ↓ ML velocity, ↔ ML full power frequency (in favour EG and WG regarding CG). | |||||||

| EG: 10 | 69.iv | EG: taekwondo | 3 | threescore | |||||||||

| WG: 10 | 71.4 | WG: walking exercise | three | sixty | twoscore–60%HRmax | Force Platform (COP) | |||||||

| CG: 10 | seventy.6 | CG: usual activities | NA | NA | |||||||||

Tabular array v. Course assessment for the certainty of evidence.

Table 5. Form assessment for the certainty of bear witness.

| Outcomes | Study Pattern | Risk of Bias in Individuals Studies | Risk of Publication Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Certainty of Evidence | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | 5 RCTs and one NRCTs with a 9 trials and 252 participants | Moderate to High i | Not assessed three | Moderate four | Low v | High 6 | Very low 7 | The OCS does non show superior effects in the older adults compared to command groups (active/passive) on balance, fall gamble, or falls. |

| Fall risk or falls | 1RCT and 2 NRCTs with a 5 trials and 91 participants | Moderate to High 2 | Not assessed 3 | Moderate 4 | Low 5 | High six | Very depression 7 |

| Publisher'due south Annotation: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and weather condition of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC Past) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-7737/11/1/74/htm

0 Response to "Health Benefits of Hard Martial Arts in Adults a Systematic Review"

Post a Comment